| Illinois Wesleyan alum Jack Sikma went to the NBA finals with Seattle twice and helped the SuperSonics beat Washington in the 1979 NBA finals. NBA Photo Library/Getty images |

By Gordon Mann, D3hoops.com

Jack Sikma wasn’t the last person to find out he had been selected eighth in the 1977 NBA Draft, but he wasn’t the first.

Long before the NBA draft was a prime time television spectacle, it played out quietly with draft hopefuls waiting patiently and privately for a phone call.

Sikma had just finished his senior season at Illinois Wesleyan University and he gathered with a few people at the home of his college coach, Dennie Bridges, to kill time playing cards, waiting for what he hoped would be good news.

With no internet or cell phones, that news would come via the University’s sports information director Ed Alsene. Alsene went to the local paper to track the draft picks via the Associated Press newswire. Alsene called Bridges’ home after each pick.

First the Milwaukee Bucks took Kent Benson out of the University of Indiana. Then Otis Birdsong went to the Kansas City Kings. Then the Bucks picked again, this time taking Marques Johnson out of UCLA.

And then silence.

- 2016 SCB Hall of Fame profile: John Rinka, Kenyon

- Small College Basketball Hall of Fame, Class of 2017

- Division III basketball playoff history

Sikma and Bridges sat, waited and wondered what happened. Eventually anxiety got the best of Bridges who called the newspaper and learned the AP wire was down.

“I don’t know if it was 45 minutes, an hour, maybe an hour and a half later. It was probably 45 minutes. It seemed like it was a couple hours. The AP wire came back up and I had been drafted,” Jack Sikma recalls. Right between Bernard King from the University of Tennessee and Tom LaGarde from the University of North Carolina.

Sikma’s selection may have been a surprise, but it was no accident. It was the culmination of a thoughtful plan to develop Jack Sikma into the best player ever at Illinois Wesleyan, a small college basketball star and eventually an NBA prospect.

“Coach told me, and it turned out to be true, ‘I don’t know where your career will go, but we’ll make sure we find how far it can go.’”

Sikma’s career took him to seven NBA All-Star teams, a world championship and a second career as an assistant coach for three NBA franchises. This summer Sikma’s career took him to South America as part of the coaching staff for the Canadian men’s national team. And this fall it’ll take him to Evansville, Indiana where he’ll be one of 12 players or coaches inducted into Small College Basketball Hall of Fame.

Basketball player first, then big man

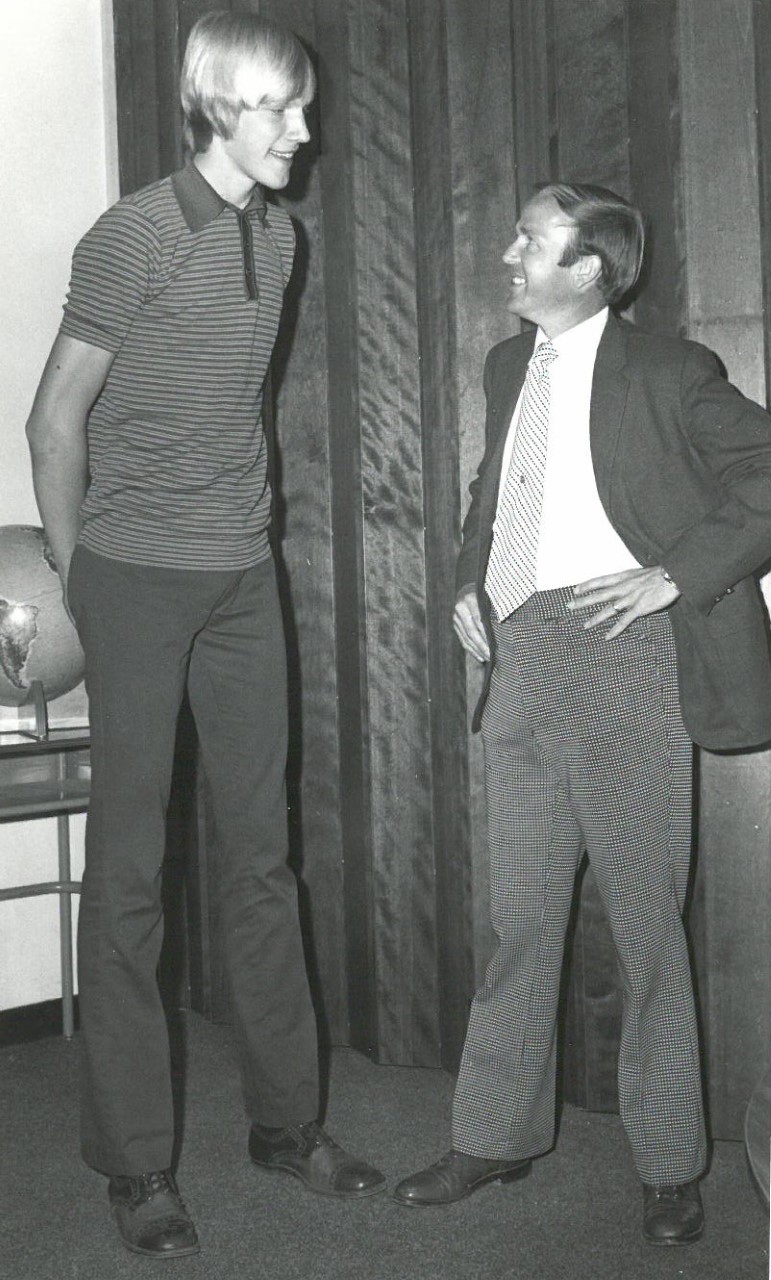

| A late bloomer, Jack Sikma still had a lot of growing to do when Dennie Bridges (right) recruited him from St. Anne High School in 1973. Photo by Illinois Wesleyan athletics |

The plan started when Bridges was trying to recruit a low post player to help his Illinois Wesleyan Titans compete with the Augustana Vikings for the College Conference of Illinois and Wisconsin (CCIW) title. Augustana was in the midst of winning the CCIW crown four consecutive years under coach Jim Borcherding.

“Augustana was our biggest rival at that time and they had a couple seven-foot guys and I said to our admissions people, ‘Hey, I wanna know anyone who’s 6'8" or over who can walk and chew gum at the same time.’”

Bridges got word of a long, lanky player named Jack Sikma playing for St. Anne High School in Kankakee County, about 100 miles east of Illinois Wesleyan’s campus in Bloomington. Bridges went to watch Sikma play in a Christmas tournament and immediately saw big things.

“I came back and told my athletic director at the time, Jack Horenberger, ‘Coach, I saw a guy play last night that, if I could recruit him, he’d be the best player in our school’s history.’”

At that time Sikma was six-foot-eight, “really skinny” as Bridges recalls, but a good shooter and very intense. During an opponent’s free throw attempts, Bridges noticed Sikma was snapping his fingers and talking to himself – miss it, miss it – trying to will the ball to himself.

Sikma describes himself as a “late bloomer.” Entering his junior year, he was a 6’1” wing player. By the end of that year, he was 6’5”. By the time he stopped growing completely, he was 6’10” and his days as a wing were over.

“I was a basketball player first before I became big man and a lot of times it doesn’t work that way. A lot of people are big men before they are basketball players. So I learned the game facing the hoop and shooting from outside.”

Sikma became Bridges’ “obsession,” as the coach calls it, and he went to watch Sikma play whenever he could, in between Illinois Wesleyan’s games and scouting the Titans’ opponents. Bridges wasn’t alone in coveting the uniquely skilled prospect. Eventually larger schools took notice, too, and the final suitors for Sikma were the University of Illinois, Kansas State, Purdue and Illinois Wesleyan.

At that time Illinois Wesleyan had dual membership in the NCAA and the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA). In 1973 the NCAA split its College Division into Division II and Division III. Illinois Wesleyan was a member of Division III, so the University couldn’t offer Sikma an athletic scholarship. The little school in Bloomington wasn’t only giving away name recognition in this recruiting battle.

But, as members of the NAIA, Illinois Wesleyan could offer Sikma the chance to play in the Association’s national championship tournament in Kansas City, Missouri and likely do so in front of NBA scouts. In Sikma’s senior year of high school, Guilford College won the 1973 NAIA title with a roster that included future NBA players Lloyd (later World B.) Free and M.L. Carr. Guilford beat Illinois Wesleyan’s rival Augustana in the NAIA tournament semifinal.

Bridges cites the NAIA tournament as the primary reason that Illinois Wesleyan was the last CCIW school to move completely to Division III. “The only reason we stayed in the NAIA was the Kansas City tournament. The Kansas City tournament was really a big thing.”

Sikma thought the NAIA’s national championship tournament was a big deal, too. Jack’s older sister attended Illinois Wesleyan for nursing, and he remembered her taking a road trip to Kansas City for the national tournament.

“I remember, when I was in high school, my parents discussing about how my sister wanted to go to the national tournament, which meant her and her girlfriends were hopping in a car, and heading to Kansas City, not sure where they were staying or whatever, but they were going to Kansas City to enjoy the spectacle.”

Sikma relished the opportunity to make the same trip as a player. Bridges sold Sikma on the chance to play right away, play winning basketball and still play bigger programs where he could showcase his skills to NBA scouts.

So Sikma decided to head to Illinois Wesleyan, told his parents and called Bridges during lunch break. Bridges was out playing golf, but his wife took the message and made sure to find out if it was good news. When Bridges returned from the course, his wife Rita gave him the message.

“Dennie, what would be the best in the world that could happen to you?” She understood her husband’s “obsession.”

"In my experience it helps to have a plan"

The season before Sikma arrived in Bloomington, Illinois Wesleyan finished tied for second in the CCIW with Elmhurst and Millikin. Augustana won the league title with a 16-0 record, which still stands as the last undefeated run through CCIW play.

Augustana overpowered the conference with 7’0” senior center John Laing and 6’11” sophomore forward Bruce Hamming. Like the NBA big men of that era, they played with their backs to the basket, close to the rim, calling for the ball to be dumped into the post so they could back down and score on a smaller opponent.

Sikma was growing into his near-seven foot frame, but he wasn’t going to fit that mold. He moved from the wing to the post and tried to find a go-to scoring move. Sikma had shot the ball from in front of his face, which worked well when he was a six-foot-eight wing, but not so much when he was lined up against seven-foot shot blockers.

“That first year I had a decent year, learning a lot, but it was evident that I didn’t have much in the post,” Sikma recalls. “In my experience, it helps to have a plan once you catch it in the post, and I had no plan whatsoever.”

So Sikma and Bridges sat down in the spring after his freshman year and tried to develop a go-to move. Bridges had seen some Illinois high school players use a move called the inside pivot. “It was kind of a move that was designed for the clod, the kid who couldn’t do anything, to keep him from making a mistake.”

Sikma was far from a clod. With the skills and shooting touch of perimeter player and the height of a center, he developed the signature move that bears his name. Catch the ball with your back to the basket. Pivot inside 180 degrees to face the rim. Step back, crane the ball behind your head and either shoot it, or if the defender bites, drive past the defender. The Sikma Move.

“Every night, for four years, I’d have him do a 100 from the right side and a 100 from the left side,” recalls Bridges. “And then, when people started crowding him to guard that shot, then Jack got to be really good at putting the ball on the floor and taking it around him.”

“We chose our course. That was step one. Step two now was making a commitment, making it become comfortable and evaluating whether it could be effective,” Sikma explains.

Illinois Wesleyan and Sikma were more than effective. The Titans won the 1975 CCIW title with a 14-2 record and Sikma was named the conference player of the year as a sophomore. After winning its first round game in the NAIA tournament, Illinois Wesleyan lost to Grand Canyon University 66-63. That was the smallest margin of victory in the NAIA tournament for Grand Canyon which went on to win the NAIA title.

Meanwhile Augustana had finished two games back of the Titans in the CCIW standings. The Vikings declared themselves eligible for the brand new NCAA Division III tournament and, with Bob Hamming in his senior season, Augustana reached the national semifinals before losing to eventual champion LeMoyne-Owen. Augustana reached the same point in 1976 when it lost in the NCAA Division III national semifinal to eventual champion, Scranton.

The next two seasons had similar results. Illinois Wesleyan won two more CCIW crowns, Sikma won two more player of the year awards and the team made two more trips to the NAIA tournament. In Sikma’s senior year the Titans entered the NAIA tournament as the second overall seed – rarefied air for the non-scholarship school from Bloomington. Illinois Wesleyan got over the hump, beating Hawaii-Hilo 85-74 in overtime to advance through the second round. But Henderson State was waiting and again knocked the Titans out of the tournament.

Sikma finished his career with 2,272 points, 1,405 rebounds and 941 field goals, all of them tops in Illinois Wesleyan basketball history. He is one of only three players to win three consecutive CCIW player of the year awards, along with North Park’s Michael Harper (who won the next three awards after Sikma graduated) and Wheaton’s Kent Raymond.

And, while Sikma didn’t get a chance to play for an NCAA Division III title, he did get a chance to play postseason games in front of NBA scouts, like Lenny Wilkins, who was the Seattle SuperSonics Director of Player Personnel in 1977.

From perplexing pick to prototype

| Sikma's versatility and ability to play away from the rim made him a prototype and a successful tutor for modern NBA big men Photo by Getty Images |

Wilkins watched Sikma play in the NAIA tournament and decided Sikma was the guy the Sonics would take with the eighth pick in the 1977 NBA draft. Sikma later told Sports Illustrated that he was less than enthusiastic when Wilkins called him before the draft to ask what he thought about his future NBA home – “Well, it’s not my first choice.”

He was greeted with equal skepticism by Seattle fans who struggled to see how this player they had never heard of, coming from a program they had never heard of, was the answer to the question, “Who do we have covering Kareem Abdul-Jabbar tonight?”

“Seattle took some flak for taking me that early. It was a bit of a surprise.”

It probably didn’t help that Sonics fans were only a couple seasons removed from watching their team trade star-center Spencer Haywood to the New York Knicks. Haywood was a four-time All-NBA center during his time in Seattle and had led the Sonics to their first ever playoff appearance in 1975 and, to that point, their only playoff round victory.

There was certainly an adjustment as Sikma transitioned from playing road games at Millikin to playing road games at Madison Square Garden. A couple weeks into the season Sikma called Bridges to say he wasn’t sure his signature move would work in the NBA. Bridges told him to stick with it.

A quarter way through Sikma’s rookie season, Lenny Wilkins took over as the team’s head coach. “Lenny Wilkins would call a play for me in the post a little bit more and pretty soon it was effective in the league,” Sikma says. He was also finally growing into his 6’10” frame and was becoming a great post defender. Sikma finished as Seattle’s all-time leader for rebounds and blocked shots.

After a 5-17 start in Sikma’s rookie season, the Sonics regrouped under Wilkins, rallied into the NBA playoffs and reached the finals where they lost in seven games to the Washington Bullets. Sikma averaged 11 points and a little under nine rebounds a game and made the 1978 All-Rookie team.

The next season Seattle cruised to a 52-30 regular season record and the top-seed in the Western Conference. Sikma made his first of seven straight all-star game appearances. After dispatching Kareem and the Lakers 4-1 in the Western Conference semifinals, Seattle outlasted Phoenix 4-3 in the Conference finals. That set up a rematch with Washington in the 1979 NBA finals, which the Sonics won handily, four games to one.

That was the pinnacle of the Sonics’ team success but Sikma continued to play at a high level in Seattle and then Milwaukee where he was traded in 1986. In an era defined by back-to-the-basket behemoths, Sikma used his guard-like skills and shooting touch to provide a different model for a successful low post player – play excellent defense in the post, develop a go-to move and become a scoring threat from the outside.

Late in his career Sikma led the NBA in free throw shooting (92.2 percent in 1988) and developed a three-point shot. He shot over 30 percent from behind the arc in his career and close to 85 percent from the foul line. “We used to have three-point shooting contests all the time in Milwaukee’s shooting practice and I shot it pretty well.”

Sikma’s unique set of skills at the center position are now coveted in the NBA where the back-to-the-basket post player is now the exception. It’s no surprise then that Sikma helped coach Yao Ming in Houston, Kevin Love in Minnesota and now Jonas Valanciunas in Toronto.

“I was one of the first [to play this style],” Sikma says. “I have a good foundation of experiences to help me coach these players. I played inside. I played outside. I was a rebounder. I got the ball on the elbow and people played through me.”

“I enjoyed competing. When you’re competing against good players, it raises your level. There’s not a better feeling then when the game’s over and you walk in the locker room and you know that you worked your tail off and executed and it was successful.”